India Loves Pakistan Meat Dishes

"When Delhi's Press Club organised an evening of Pakistani food and music, flying in chefs from Islamabad, the racks of richly-spiced meat on the grill quickly ran out as hundreds of Indian journalists brought their families, equipped with "tiffin" boxes to take away extra supplies" BBC Report 26 June 2014

The BBC story highlights the fact that the vegetarian India demonstrates its deep love of the exquisite taste of Pakistan's meat dishes whenever the opportunity presents itself. To further illustrate the phenomenon, let me share with my readers how two famous Indians see meat-loving Pakistan:

Sachin Tendulkar:

The senior cricketer...said he gorged on Pakistani food and had piled on a few kilos on his debut tour there. "The first tour of Pakistan was a memorable one. I used to have a heavy breakfast which was keema paratha and then have a glass of lassi and then think of dinner. After practice sessions there was no lunch because it was heavy but also at the same time delicious. I wouldn't think of having lunch or snack in the afternoon. I was only 16 and I was growing," Tendulkar recalled. "It was a phenomenal experience, because when I got back to Mumbai and got on the weighing scale I couldn't believe myself. But whenever we have been to Pakistan, the food has been delicious. It is tasty and I have to be careful for putting on weight," he said.

Source: Press Trust of India November 2, 2012

Hindol Sengupta:

Yes, that's right. The meat. There always, always seems to be meat in every meal, everywhere in Pakistan. Every where you go, everyone you know is eating meat. From India, with its profusion of vegetarian food, it seems like a glimpse of the other world. The bazaars of Lahore are full of meat of every type and form and shape and size and in Karachi, I have eaten some of the tastiest rolls ever. For a Bengali committed to his non-vegetarianism, this is paradise regained. Also, the quality of meat always seems better, fresher, fatter, more succulent, more seductive, and somehow more tantalizingly carnal in Pakistan. I have a curious relationship with meat in Pakistan. It always inevitably makes me ill but I cannot seem to stop eating it. From the halimto the payato the nihari, it is always irresistible and sends shock shivers to the body unaccustomed to such rich food. How the Pakistanis eat such food day after day is an eternal mystery but truly you have not eaten well until you have eaten in Lahore!

Source: The Hindu August 7, 2010

Silicon Valley Indians:

I personally see vivid proof of how much Indians love Pakistani food every time I go to Pakistan restaurants serving chicken tikka, seekh kabab, biryani and nihari in Silicon Valley, California. Among the Pakistani restaurants most frequented by Indians are Shalimar, Pakwan and Shan. These restaurants are also very popular with white Americans and East Asians in addition to other ethnic groups including Afghans, Middle Easterners and South Asians.

Carnivorous Pakistanis:

A recent study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and Nature magazine reported that Pakistanis are among the most carnivorous people in the world.

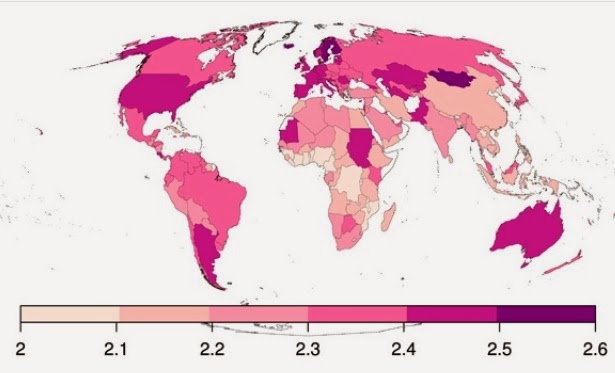

The scientists conducting the study used "trophic levels" to place people in the food chain. The trophic system puts algae which makes its own food at level 1. Rabbits that eat plants are level 2 and foxes that eat herbivores are 3. Cod, which eats other fish, is level four, and top predators, such as polar bears and orcas, are up at 5.5 - the highest on the scale.

After studying the eating habits of 176 countries, the authors found that average human being is at 2.21 trophic level. It put Pakistanis at 2.4, the same trophic level as Europeans and Americans. China and India are at 2.1 and 2.2 respectively.

The countries with the highest trophic levels (most carnivorous people) include Mongolia, Sweden and Finland, which have levels of 2.5, and the whole of Western Europe, USA, Australia, Argentina, Sudan, Mauritania, Kazakhstan, Pakistan and Turkmenistan, which all have a level of 2.4.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) also published recent report on the subject of meat consumption. It found that meat consumption in developing countries is increasing with rising incomes. USDA projects an average 2.4 percent annual increase in developing countries compared with 0.9 percent in developed countries. Per capita poultry meat consumption in developing countries is projected to rise 2.8 percent per year during 2013-22, much faster than that of pork (2.2 percent) and beef (1.9 percent).

Summary:

Although meat consumption in Pakistan is rising, it still remains very low by world standards. At just 18 Kg per person, it's less than half of the world average of 42 Kg per capita meat consumption reported by the FAO.

While Pakistanis are the most carnivorous people among South Asians, their love of meat is spreading to India with its rising middle class incomes. Being mostly vegetarian, neighboring Indians consume only 3.2 Kg of meat per capita, less than one-fifth of Pakistan's 18 Kg. Daal (legumes or pulses) are popular in South Asia as a protein source. Indians consume 11.68 Kg of daal per capita, about twice as much as Pakistan's 6.57 Kg.

India and China with the rising incomes of their billion-plus populations are expected to be the main drivers of the worldwide demand for meat and poultry in the future.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

Indians Share Eye-Opening Stories of Pakistan

Pakistan Among Top Meat and Dairy Consuming Nations

Pakistan Leads South Asia in Value Added Agriculture

Livestock and Agribusiness Revolution in Pakistan

Pakistan's Rural Economy Showing Strength

Solving Pakistan's Sugar Crisis

Food, Clothing and Shelter in India and Pakistan

Is India a Nutritional Weakling?

India Tops World Hunger Charts

The BBC story highlights the fact that the vegetarian India demonstrates its deep love of the exquisite taste of Pakistan's meat dishes whenever the opportunity presents itself. To further illustrate the phenomenon, let me share with my readers how two famous Indians see meat-loving Pakistan:

Sachin Tendulkar:

The senior cricketer...said he gorged on Pakistani food and had piled on a few kilos on his debut tour there. "The first tour of Pakistan was a memorable one. I used to have a heavy breakfast which was keema paratha and then have a glass of lassi and then think of dinner. After practice sessions there was no lunch because it was heavy but also at the same time delicious. I wouldn't think of having lunch or snack in the afternoon. I was only 16 and I was growing," Tendulkar recalled. "It was a phenomenal experience, because when I got back to Mumbai and got on the weighing scale I couldn't believe myself. But whenever we have been to Pakistan, the food has been delicious. It is tasty and I have to be careful for putting on weight," he said.

Source: Press Trust of India November 2, 2012

Hindol Sengupta:

Yes, that's right. The meat. There always, always seems to be meat in every meal, everywhere in Pakistan. Every where you go, everyone you know is eating meat. From India, with its profusion of vegetarian food, it seems like a glimpse of the other world. The bazaars of Lahore are full of meat of every type and form and shape and size and in Karachi, I have eaten some of the tastiest rolls ever. For a Bengali committed to his non-vegetarianism, this is paradise regained. Also, the quality of meat always seems better, fresher, fatter, more succulent, more seductive, and somehow more tantalizingly carnal in Pakistan. I have a curious relationship with meat in Pakistan. It always inevitably makes me ill but I cannot seem to stop eating it. From the halimto the payato the nihari, it is always irresistible and sends shock shivers to the body unaccustomed to such rich food. How the Pakistanis eat such food day after day is an eternal mystery but truly you have not eaten well until you have eaten in Lahore!

Source: The Hindu August 7, 2010

Silicon Valley Indians:

I personally see vivid proof of how much Indians love Pakistani food every time I go to Pakistan restaurants serving chicken tikka, seekh kabab, biryani and nihari in Silicon Valley, California. Among the Pakistani restaurants most frequented by Indians are Shalimar, Pakwan and Shan. These restaurants are also very popular with white Americans and East Asians in addition to other ethnic groups including Afghans, Middle Easterners and South Asians.

Carnivorous Pakistanis:

A recent study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and Nature magazine reported that Pakistanis are among the most carnivorous people in the world.

The scientists conducting the study used "trophic levels" to place people in the food chain. The trophic system puts algae which makes its own food at level 1. Rabbits that eat plants are level 2 and foxes that eat herbivores are 3. Cod, which eats other fish, is level four, and top predators, such as polar bears and orcas, are up at 5.5 - the highest on the scale.

|

| Trophic Levels Map Source: Nature Magazine |

|

| Source: Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences |

The countries with the highest trophic levels (most carnivorous people) include Mongolia, Sweden and Finland, which have levels of 2.5, and the whole of Western Europe, USA, Australia, Argentina, Sudan, Mauritania, Kazakhstan, Pakistan and Turkmenistan, which all have a level of 2.4.

United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) also published recent report on the subject of meat consumption. It found that meat consumption in developing countries is increasing with rising incomes. USDA projects an average 2.4 percent annual increase in developing countries compared with 0.9 percent in developed countries. Per capita poultry meat consumption in developing countries is projected to rise 2.8 percent per year during 2013-22, much faster than that of pork (2.2 percent) and beef (1.9 percent).

Summary:

Although meat consumption in Pakistan is rising, it still remains very low by world standards. At just 18 Kg per person, it's less than half of the world average of 42 Kg per capita meat consumption reported by the FAO.

While Pakistanis are the most carnivorous people among South Asians, their love of meat is spreading to India with its rising middle class incomes. Being mostly vegetarian, neighboring Indians consume only 3.2 Kg of meat per capita, less than one-fifth of Pakistan's 18 Kg. Daal (legumes or pulses) are popular in South Asia as a protein source. Indians consume 11.68 Kg of daal per capita, about twice as much as Pakistan's 6.57 Kg.

India and China with the rising incomes of their billion-plus populations are expected to be the main drivers of the worldwide demand for meat and poultry in the future.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

Indians Share Eye-Opening Stories of Pakistan

Pakistan Among Top Meat and Dairy Consuming Nations

Pakistan Leads South Asia in Value Added Agriculture

Livestock and Agribusiness Revolution in Pakistan

Pakistan's Rural Economy Showing Strength

Solving Pakistan's Sugar Crisis

Food, Clothing and Shelter in India and Pakistan

Is India a Nutritional Weakling?

India Tops World Hunger Charts

Comments

The new spot, located at 340 O’Farrell St. in the old Naan N Curry, will be the first step in what’s a miniature Bay Area takeover for the East Coast food cart. (They have plans for another spot in Berkeley). Right now, the Halal Guys have 200 locations in development across the U.S., Canada and Southeast Asia.

We’ve been following the news of Halal Guys setting up shop in the Bay Area for the last few months now. This latest update means they’re less than a month from dishing out those renowned chicken gyros or falafel between Taylor and Mason streets for both Union Square and Tenderloin audiences.

Stay tuned for more coverage.

Halal Guys: 340 O’Farrell St., Sunday through Wednesday from 10 a.m. to 2 a.m. and Thursday through Saturday from 10 a.m. to 4 a.m.

Pakistan becomes third-largest importer of cooking oil

https://tribune.com.pk/story/1302877/high-consumption-pakistan-becomes-third-largest-importer-cooking-oil/

KARACHI: Pakistan has become the third largest importer of cooking oil after China and India, a statement said on Saturday.

“The import of crude and refined cooking oil has increased to 2.6 million tons per annum in Pakistan,” Westbury Group Chief Executive Rasheed Jan Mohammad said at a one-day conference on edible oil.

Balance of payments: Current account deficit widens 92%

Pakistan also imports 2.2 million tons oil seeds every year, he said.

Imports help the country meet around 75% of its domestic needs. The remaining need is met through locally produced banola and mustard oils.

Pakistan imports crude and refined cooking oils (palm and palm olein) mainly from Malaysia and Indonesia and brings in soybean oil from North America and Brazil.

Jan Mohammad said approximately 30% of the import bill is comprised of taxes that traders pay at Pakistan’s sea ports. “The government should rationalise the taxes,” he said.

Dr James Fry, Chairman of LMC International, a research institute of the UK, said fluctuation in production, demand and price of edible oils has a direct link with crude fuel oils in the world. “The production and supply of palm oil would increase in 2017,” he projected.

The statement issued by Pakistan Edible Oil Conference (PEOC) quoted speakers at the conference, saying that Pakistan needs to set up one more import terminal at sea ports to keep the flow of goods smooth.

Apparel sector: Govt urged to withdraw duty on cotton yarn import

They said that Pakistan has so far invested Rs50 billion in import, processing and storage industries of edible oil. They estimated a similar quantum of investment in the years to come. Trade Development Authority of Pakistan Chief Executive SM Muneer said revival of the local economy, increased disposable income, surging demand for cooking oil and rising population have created opportunities for more investment in the edible oil industry in Pakistan.

Zubair Tufail, President, Federation of Pakistan Chambers of Commerce and Industry, said that per-capita consumption of cooking oil in Pakistan is among the highest in the world.

He said Malaysia and Indonesia remained two big sources of import of the oil into the Pakistan. He asked Malaysia and Indonesia to increase investment in the edible oil industry in Pakistan, as they can take benefit of transit trade to Afghanistan and Central Asian countries via Pakistan.

Outstanding bills: Disruption in oil supplies to power plants feared

Sheikh Amjad Rafique, a speaker at the conference, said Malaysia has imposed taxes on export of oil to Pakistan. “This is a negation of the Free Trade Agreement (FTA) between Pakistan and Malaysia,” he said.

He said the Pakistani government needs to engage with Malaysia to remove this anomaly and exploit full benefit of the agreement in place.

33-year-old Syed Asim Hussain recently become the youngest restaurateur in the world to hold two Michelin stars.

In December, his ambitious and extremely personal Pakistani restaurant New Punjab Club was awarded a Michelin Star, just 18 months after it opened its doors in one of Hong Kong’s prime localities.

With this, the New Punjab Club is also the first Pakistani restaurant in the world with a Michelin Star. Hussain’s other Michelin honour has been awarded for his French bistro, Belon.

Hussain shared his excitement about the Michelin honour with Images in an exclusive chat over the phone from Hong Kong, "I feel very proud to have received two stars this year. I sort of expected it for the French restaurant, but to have the New Punjab Club recognised so early on is exciting.

Hussain continues, "It’s the first Pakistani restaurant to have a Michelin Star, and I was just telling my team that we have to make sure it stays. Initially, I was convinced someone was pranking us, or we got a call by mistake. I didn’t believe it until the morning of the awards. It was a cool honour for me personally as well. In some ways, it belongs to my father also, for the work he was doing with his restaurants in the ‘80s and ‘90s in Hong Kong. Still talking about it gives me chills; it sure is hard to believe.”

The New Punjab Club and Belon are just two of the 22 restaurants under the Black Sheep Restaurants umbrella that Hussain co-founded with his business partner, Christopher Mark, in 2012.

Hussain was born in Hong Kong, but spent his formative years in Pakistan when his father, businessman and diplomat Syed Pervaiz Hussain, sent him - at age five - and his six-year-old brother off to boarding school at Lahore’s Aitchison College.

“The key element in the story of the New Punjab Club is nostalgia, of which Aitchison is a very big part of. Everyone at the restaurant knows about the school; they’ve seen pictures. My Aitchison stories have now become their Aitchison stories. So, the 13-14 years I spent there, have helped create the New Punjab Club. The essence that comes from Aitchison is very aristocratic and regal. As a kid, I also spent a lot of time at the Punjab Club in Lahore, which is why I affectionately named the restaurant after it.”

Before opening up the restaurant, the duo already had 15 restaurants to their credit under their group. Yet, Hussain says it wasn’t easy convincing Chris to open up a restaurant that serves Pakistani and Indian cuisine. “Pakistani cuisine is white-labelled all over the world as Indian food. I had been talking to [Chris] about this and had a hard time convincing him. So, I took him to Lahore in 2016, and in a week I showed him around Aitchison, Punjab Club, Gowalmandi, Lakshmi Chowk and even Cocoo’s. I was trying to make him look at this the way I did, to show him that we could build a story around this.”

The research and convincing didn’t end at Lahore. “We then went to London. The city has neighbourhoods that have great Pakistani food, which is not white-labelled as Indian food. We saw great modern Indian restaurants like the renowned Gymkhana, Dishoom, and Indian Accent among many others. This was all part of my attempt to convince him that we could do this - we would tell an original, interesting and sellable story.”

The duo was lucky, and got Chef Palash Mitra, of London’s Gymkhana on board for the restaurant. In Hussain’s words, “Mitra is one of the best South Asian chefs in the world.”

Hussain talked about the hurdles they faced during menu development, “We couldn’t get the seekh kabab right; they weren’t the same as they are in Main Market, Lahore. I then realised the issue was that the diameter of the seekh in Lahore is larger than that in India. So, I got some seekhs from Lahore just for this.”

She mostly credits customer loyalty for Zareen’s current stability. One customer even asked a couple of weeks ago if she could make a large donation to the restaurant to make sure it survives.

“I will not accept it but just the gesture. ...” Khan said, trailing off. “It was a very emotional moment for me and made me realize we’re not just serving food, we’re serving our community. The way they’ve taken care of me is precious.”

Each time the supply of this particular masala blend becomes erratic in Bengaluru, foodie groups on Facebook and WhatsApp start buzzing. “I found two packets of Sindhi Biryani Masala at Aishwarya supermarket in Koramangala." “Mega More on Sarjapur Road has Haleem and Bombay Biryani." “Amazon has some varieties but they are only selling packs of 8, anyone want to split up the order?"

Over the past decade, Shan, a packaged masala brand from Pakistan, has slowly invaded Indian kitchens. Fans of Shan follow developments in India-Pakistan relations with a hawk eye, because often, escalating tensions at the border seem to result in the supply of Pakistani products in India becoming sparse and unpredictable. Last year, a few days after the attack on Indian forces in Pulwama, my husband turned to me and said, “How are we doing on Shan?", a quiver of anxiety in his voice. I had stocked up on the biryani and korma masalas, I assured him, but we were running low on the haleem.

More than a year later, the Shan Haleem masala remains elusive (maybe it’s the covid-19 effect this time) and my annual haleem-making adventure during Ramzan had to be put on hold. Friends in Mumbai and Delhi, however, say Shan is “more or less available" in their cities. This felt patently unfair and I recently discovered why Bengaluru had these periodic shortages. According to an interview with Shan Foods’ founder Sikander Sultan by the Economic Times in 2014, while the company has made inroads into the north-Indian market and was even leading in certain sub-categories within the packaged masala blend segment, they hadn’t expanded to “some geographies like the south."

The company, it seems, is not actively distributing the product in southern Indian cities, and it’s only thanks to some enterprising retailers that a few of the masala varieties are available at all in Bengaluru, and this naturally suffers when the overall supply falls because of border tensions.

If Mr Sultan ever reads this, he should know that he is losing out on a lucrative and highly motivated market. “I have asked my sister to courier them to me from Delhi," says Bengaluru-based food consultant and writer Monika Manchanda. “I’ve been looking for them all over town but they seem to have disappeared from the shelves." I recently reached out to a seller on Amazon that stocks Shan but sells them only in 8 packs of a single variety and asked if they would customise an 8-pack for me. They did, and just a couple of days ago a carton of Shan made its way home (two each of the Bombay Biryani, Korma, Chicken, and Nihari masalas, if you want to know).

But what’s so special about Shan masalas in the first place, ask the uninitiated, sounding skeptical—isn’t it like any other meat masala that you sprinkle on top of your curry for that extra flavour and restaurant-like taste? “Just because it’s Pakistani?" a full-of-nationalistic-fervour neighbour recently asked me when I was extolling Shan’s virtues on a WhatsApp group, possibly suspecting me of deliberately snubbing made-in-India atmanirbhar products.

The Shan Foods company sells spice mixes in 65 countries including India, a nation with whom Pakistan shares decades of enmity that is dominated by their territorial dispute over Kashmir. They have fought three wars since their independence from Britain in 1947.

“I wasn’t aware it’s a Pakistani brand,” Kumar told Arab News, saying her family loved dishes cooked with Shan spices and that she always kept extra stock of the mixes at home. “How does it matter whether it is Pakistani or Indian? The taste is good. Both the neighbors share the same taste and culture and I feel both countries should have access to their products,” she added.

Kumar’s family is a supporter of India’s nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), under whose rule the already brittle ties with Pakistan have deteriorated further in recent years.

Even so, Kumar said, there was no harm in using Pakistani products.

“Both India and Pakistan share the same history, same past, and the same taste. What’s wrong if we get Pakistani products in our kitchen or house? This should be promoted so that both countries could understand each other better.”

One shop owner said that, although he did not like selling Pakistani brands, customers came asking for Shan spices.

“I don’t like to keep the brand, but customers demand it,” Naresh Sankhla told Arab News at his New Delhi grocery store. “That’s why I keep it. I reluctantly sell this brand from the enemy country, but there is demand for it. I must be selling around 150 packets of Shan (spices) every month.”

Others say that, despite the brand’s popularity, they put India first.

“I have stopped distributing the Shan brand last year after Pakistan’s involvement in the Pulwama tragedy,” New Delhi-based distributor Gaurav Gupta told Arab News, referring to last year’s attack in a town in the Indian part of Kashmir in which 50 Indian paramilitary soldiers were killed. New Delhi has blamed Pakistan-based groups for the assault. The Pakistan government denies any official complicity.

Despite his official words, however, quick market research showed that Gupta’s company remains one of the main sellers of Shan’s products.

Rafat Shahab, who runs a catering company, regretted such negative attitudes and said that culinary exchanges needed to be encouraged despite the two countries’ political differences.

“I used the Shan brand a lot whenever I got orders for parties or special occasions,” she told Arab News. “It brings an authentic taste in the food. It’s unfortunate that we don’t have that kind of relationship with Pakistan. Politics should not come in the way of people’s contacts and culinary exchanges.”

by Carolyn Beans

https://www.npr.org/sections/thesalt/2016/06/22/482779599/meet-hing-the-secret-weapon-spice-of-indian-cuisine

The moment my boyfriend — now husband — and I got serious about our future together, my father-in-law got serious about teaching me to cook Indian cuisine. My boyfriend was already skilled in the kitchen. But Dr. Jashwant Sharma wanted extra assurance that the dishes from his native country would always have a place in our home. Plus, as he told me recently, he thought I'd like it.

"We mix four, five, six different spices in a single dish. These create a taste and aroma that you don't get in any other food. People exposed to it usually like it," he said.

Even before our cooking sessions, I knew that cumin and coriander are common ingredients and that turmeric will turn your fingers yellow. Hing, however, was something entirely new to me.

Europeans gave it the decidedly unflattering moniker "devil's dung." Even its more common English name, asafoetida, is derived from the Latin for fetid. Those unaccustomed to it can respond negatively to its strong aroma, a mix of sulfur and onions.

Hing comes from the resin of giant fennel plants that grow wild in Afghanistan and Iran. The resin can be kept pure, but in the States, you mostly find it ground to a powder and mixed with wheat. In The Book of Spice, author John O'Connell describes how Mughals from the Middle East first brought hing to India in the 16th century.

Many Indians use hing to add umami to an array of savory dishes. But for the uninitiated, hing can be a tough sell. Kate O'Donnell, author of The Everyday Ayurveda Cookbook, says that she only included hing as an optional spice. "For a Western palette, hing can be shocking," she says

I first encountered hing in one of our early cooking sessions. My father-in-law whipped its well-sealed white plastic bottle out of the cupboard, added a pinch to the pan, and put it back so quickly that I didn't notice the smell. I was most struck by how it bubbled and then dissolved in the hot ghee (clarified butter). And I was a bit skeptical that a pinch of anything could influence a giant pot of lentils liberally seasoned with three other spices.

Later, while experimenting on my own, I got my first full whiff of the spice. To me, the aroma is far from gag-inducing, but it takes a real leap of faith to add it to food. Once you make that leap, magical things happen.

When cooked, hing's pungent odor mellows to a more mild leek- and garlic-like flavor. Some still smell a hint of sulfur, but for many that quality fades entirely. My father-in-law says that hing has a balancing effect on a dish. "It smooths out the aroma of all the other spices and makes them all very pleasant," he says.

Vikram Sunderam, a James Beard Award winner and chef at the Washington, D.C., Indian restaurants Rasika West End and Rasika Penn Quarter, says that he adds hing to lentil or broccoli dishes. But he uses it judiciously.

"Hing is a very interesting spice, but it has to be used in the right quantity," he cautions. "Even a little bit too much overpowers the whole dish, makes it just taste bitter."

Some believe that hing helps with digestion and can ward off flatulence. Perhaps that's why many — including Sunderam — add it to legumes, broccoli and other potentially gas-inducing vegetables.

Some Indians also use it as a substitute for garlic and onions — ingredients discouraged by certain Eastern religions and Ayurvedic medicine.

That substitution makes sense to Gary Takeoka, a food chemist with the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Takeoka studied hing's volatiles — the chemical compounds that produce smells. "A major proportion of hing's volatiles are sulfur compounds," he explains. "Some of these are similar to the ones found in onions and garlic."

There aren’t many opportunities to enjoy Pakistani food here in Missoula - in fact there are none - but one UM alum is trying to change that.

"I think it started with the whole idea of bringing my culture to Missoula," Zeera Food Truck creator Zohair Bajwa said. Bajwa is currently crowdfunding his dream of bringing Pakistani food to Missoula.

There weren’t any options for Pakistani food when Bajwa began attending the University of Montana about a decade ago so he started making it himself and when friends loved the food too he had an idea.

"It was very encouraging to see friends asking hey whens the next time you are going to make food and when can we come over. Just for the cultural aspect guests are always welcome so it was another chance to share my culture," Bajwa said.

So Zohair is looking to start with a food truck named 'Zeera' which will offer a number of dishes. "Predominantly we will be serving curry style chicken lentils for vegetarian options. Samosas are becoming popular here in Montana," Bajwa added.

Currently, Bajwa is crowdfunding to start the food truck and while a first campaign didn’t raise all the money needed, it was promising enough to hope a second will complete the goal.

https://www.sfchronicle.com/restaurants/article/Halal-food-used-to-be-scarce-in-the-Bay-Area-Now-15785763.php

When Abbas Mohamed moved to Dublin as a teenager, there were barely any halal restaurants he and his family would visit. There were a few in San Francisco and some more dotted around the bay, but options were limited, both in their number as well as in the range of cuisines they offered, such as the Indo-Pakistani restaurant Shalimar in San Francisco or the halal Chinese restaurant Darda in Milpitas.

Fifteen years later, the situation is completely different — in part thanks to a growing community Mohamed launched in 2018 called Bay Area Halal Foodies. Congregating on Facebook, the group is introducing what could be the country’s first halal restaurant week, running in the Bay Area from Dec. 9 to 13. The event is a way for the community to share news about halal food businesses, rate restaurants and promote their own food ventures. When organizing the restaurant week, which promotes discounts and other offers at participating businesses, Mohamed counted more than 100 Bay Area halal restaurants.

“These are just the ones we know about. We’re still discovering new ones every day,” he said.

Halal restaurants serve meat that was slaughtered according to Islamic tradition. There are different opinions on how these traditions and rules are interpreted, but one of the rules in the group is to not argue about standards. The group was born out of necessity during Ramadan, Mohamed said, when many members of the Bay Area’s Muslim community wanted to know which restaurants were open late — places where they could break the fast from sunset until sunrise, when fasting starts again.

“Who’s open at 4 in the morning? No other person in their sane mind is asking that question,” Mohamed said.

It took until 2020 and the pandemic for the group to really take off: In January, it had 1,000 members and has since grown to 8,000.

“Not only were people looking for dining options, or reasons to leave the house,” he said, “a lot of home cooks are starting their businesses and promoting it on there, too.”

In the group, supply and demand is visible in real time, and prospective chefs and food businesses can gauge interest in their ideas and their offer. A few months ago, for example, a member asked the group if there would be a demand for halal smoked brisket, and after a sizable number of people on the group showed their interest, she started her new venture called Off the Menu Halal based out of a home kitchen in Cupertino.

Mohamed also notes that four places specializing in halal birria tacos have opened in the past few months.

Innovations like that show the evolution of the Bay Area’s halal food scene: Restaurants used to opt for more traditional menus, replicating the taste of the home countries. One of the first restaurants to go a different route and fuse halal practices with American food culture is Mirchi Cafe with its two locations in Fremont and Dublin. Run by Lisa Ahmad, an Italian American chef and convert to Islam, the restaurant’s menu signifies the power of food as a melting pot of cultures.

Ahmad grew up in a family of Italian restaurant owners, and later attended San Francisco’s now closed California Culinary Academy before starting a series of food businesses. She finally settled on Mirchi Cafe in 2004, where she combines the food of her childhood with the Pakistani culture and cuisine of her husband. The menu features creations such as Punjabi burgers made with ground chicken with onions, chiles and house-made masala, fries with masala mix, and pizza with a chicken tikka topping.

https://www.businesstimes.com.sg/life-culture/worlds-first-michelin-star-for-a-pakistani-restaurant

Like many of Hong Kong's 85,000 strong South Asian population, Mr Hussein's family trace their lineage in the bustling financial hub back generations, when the city was a British colonial outpost.

His great-grandfather arrived during World War One, overseeing mess halls for British soldiers while his Cantonese speaking father owned restaurants in the eighties and nineties.

Mr Hussein, 33, already had some twenty eateries in his group when he decided to embark on his what he described as his most personal and risky project yet, a restaurant serving dishes from Pakistan's Punjab region, the family's ancestral homeland and where he was packed off to boarding school aged six.

---------------------

Those tandoors, frequent trips to Lahore to perfect recipes and a kitchen overseen by head chef Palash Mitra, earned the New Punjab Club a Michelin star just 18 months after it opened its doors.

The success made headlines in Pakistan, a country that is unlikely to see a Michelin guide any time soon and whose chefs have long felt overshadowed by the wider global recognition gained from neighbouring India's regional cuisines.

"It makes us proud, it makes us very happy," Waqar Chattha, who runs one of Islamabad's best-known restaurants, told AFP. "In the restaurant fraternity it's a great achievement. It sort of sets a benchmark for others to achieve as well."

Mr Hussain is keen to note that his restaurant only represents one of Pakistan's many cuisines, the often meat-heavy, piquant food of the Punjab. At it doesn't come cheap - as much as US$100 per head.

"I'm not arrogant or ignorant to say this is the best Pakistani restaurant in the world. There are better Pakistani restaurants than this in Pakistan."

----------------

A great source of pride for HK's Pakistani community

But he says the accolade has still been a "great source of pride" for Hong Kong's 18,000-strong Pakistani community.

"It's bringing a very niche personal story back to life, this culture, this cuisine is sort of unknown outside of Pakistan, outside of Punjab, so in a very small way I think we've shed a positive light on the work, on who we are and where we come from," he explains.

It was the second star achieved by Black Sheep, the restaurant group which was founded six years ago by Mr Hussein and his business partner, veteran Canadian chef Christopher Mark, and has seen rapid success.

But the expansion of Michelin and other western food guides into Asia has not been without controversy.

Critics have often said reviewers tended to over-emphasise western culinary standards, service and tastes.

Daisann McLane is one of those detractors. She describes the Michelin guide's arrival in Bangkok last year as "completely changing the culinary scene there - and not in a good way."

She runs culinary tours to some of the Hong Kong's less glitzy eateries - to hole-in-the-wall dai pai dong food stalls, African and South Asian canteens hidden inside the famously labyrinthine Chungking Mansions and to cha chan teng tea shops famous for their sweet brews and thick slabs of toast.

-----

For some, any recognition of Pakistan's overlooked cuisine is a success story.

Sumayya Usmani said she spent years trying to showcase the distinct flavours of Pakistani cuisine, so heavily influenced by the tumultuous and violent migration sparked by the 1947 partition of India.

When the British-Pakistani chef first pitched her cookbook to publishers on her country's cuisine, many initially balked.

http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20210309-pakistans-beloved-poor-mans-burger

Pakistan's beloved 'poor man’s burger'

For Pakistanis, especially Karachiites, the iconic bun-kebab isn’t just a food but an expression of their identity.

Bun-kebabs, widely considered the most beloved Pakistani street food, are thin shami kebab or potato patties in fluffy, milky buns with tangy chutney and crisp vegetables. Optional fried eggs add an extra protein hit. The combination of explosive South Asian flavours, chutney-drenched buns and vegetarian options create a starkly different culinary experience from that of a burger. Ubiquitously available at kiosks and small shops or peddled on pushcarts throughout the country, they are generally sold for between 50 and 120 Pakistani rupees (£0.23-£0.55), depending on the neighbourhood.

Potato bun-kebabs have long been staples at school canteens, and travellers in Pakistan will see women perched on wooden benches feasting on them in crowded shopping plazas. They’re accessible enough to grab for a quick bite, but not so heavy – on the pocket or the stomach – to require serious investment. “You don’t need to book a reservation or plan out your monthly savings to have a really good bun-kebab,” said Riffat Rashid, the food content creator behind Girl Gotta Eat.

For many Pakistanis, bun-kebabs are intertwined with nostalgic family memories, often representing a first experience of eating out or getting takeaway. Osamah Nasir, who founded the Karachi Food Guide in 2013, remembers first eating bun-kebabs during load-shedding (power outages) at his maternal grandmother’s house when he was a child, where nearly a dozen of his cousins spent lazy Sunday afternoons. “In less than 100 Pakistani rupees (£0.46), we’d all be fed,” he said.

Pinpointing a definitive moment in history when bun-kebabs originated is difficult. Some consider them Pakistan’s affordable (and zestier) answer to burgers, especially because of the unique phenomenon of bun-kebab stalls positioned right outside fast-food franchises. Others, like Haji-Adnan, the third-generation owner of an unnamed bun-kebab stall in Burns Road (a food street in Karachi) think they came about in the 1950s. Haji-Adnan believes his grandfather, Haji Abdul Razzak, introduced them as a mess-free, to-go option for bustling workers in the city centre in 1953, before fast food joints started proliferating across Pakistan’s cities.

Its original recipe, more than a century old, is tucked away in a highly secure, temperature-controlled family archive in India’s capital.

But the sugary summer cooler Rooh Afza, with a poetic name that means “soul refresher” and evokes the narrow alleys of its birthplace of Old Delhi, has long reached across the heated borders of South Asia to quench the thirst of generations.

In Pakistan, the thick, rose-colored syrup — called a sharbat or sherbet and poured from a distinctive long-neck bottle — is mixed with milk and crushed almonds as an offering in religious processions.

In Bangladesh, a new groom often takes a bottle or two as a gift to his in-laws. Movies even invoke it as a metaphor: In one film, the hero tells the heroine that she is beautiful like Rooh Afza.

And in Delhi, where the summer temperatures often exceed 100 degrees Fahrenheit and the city feels like a slow-burning oven, you can find it everywhere.

The chilled drink is served in the plastic goblets of cold-drink vendors using new tricks to compete for customers — how high and how fast they can throw the concentrate from one glass to the next as they mix, how much of it they can drizzle onto the cup’s rim.

The same old taste is also there in new packaging to appeal to a new generation and to new drinkers: in the juice boxes in children’s school bags, in cheap one-time sachets hanging at tobacco stalls frequented by laborers, and in high-end restaurants where it’s whipped into the latest ice cream offering.

As summer heat waves worsen, the drink’s reputation as a natural, fruits-and-herbs cooler that lowers body temperature and boosts energy — four-fifths of it is sugar — means that even a brief interruption in manufacturing results in huge outcries over a shortage.

Behind the drink’s survival, through decades of regional violence and turmoil since its invention, is the ambition of a young herbalist who died early, and the foresight of his wife, the family’s matriarch, to help her young sons turn the beverage into a sustainable business.

The drink brings about $45 million of profit a year in India alone, its manufacturer says, most of it going to a trust that funds schools, universities and clinics.

“It might be that one ingredient or couple of ingredients have changed because of availability, but by and large the formula has remained the same,” said Hamid Ahmed, a member of the fourth generation of the family who runs the expanded food wing of Hamdard Laboratories, which produces the drink.

In the summer of 1907 in Old Delhi, still under British rule, the young herbalist, Hakim Abdul Majid, sought a potion that could help ease many of the complications that come with the country’s unbearable heat — heat strokes, dehydration, diarrhea.

What he discovered, in mixing sugar and extracts from herbs and flowers, was less medicine and more a refreshing sherbet. It was a hit. The bottles, glass then and plastic now, would fly off the shelves of his small medicine store, which he named Hamdard.

Mr. Majid died 15 years later, at the age of 34. He was survived by his wife, Rabea Begum, and two sons; one was 14, and the other a toddler. Ms. Begum made a decision that turned Hamdard into an enduring force and set a blueprint for keeping it profitable for its welfare efforts at a time when politics would tear the country asunder.

She declared Hamdard a trust, with her and her two young sons as the trustees. The profits would go not to the family but largely to public welfare.

The company’s biggest test came with India’s bloody partition after independence from the British in 1947. The Muslim nation of Pakistan was broken out of India. Millions of people endured an arduous trek, on foot and in packed trains, to get on the right side of the border. Somewhere between one million and two million people died, and families — including Ms. Begum’s — were split up.

Hakim Abdul Hamid, the older son, stayed in India. He became a celebrated academic and oversaw Hamdard India.

Hakim Mohamad Said, the younger son, moved to the newly formed Pakistan. He gave up his role in Hamdard India to start Hamdard Pakistan and produce Rooh Afza there. He rose to become the governor of Pakistan’s Sindh Province but was assassinated in 1998.

When in 1971 Pakistan was also split in half, with Bangladesh emerging as another country, the facilities producing Rooh Afza in those territories formed their own trust: Hamdard Bangladesh.

All three businesses are independent, run by extended members, or friends, of the young herbalist’s family. But what they offer is largely the same taste, with slight variations if the climate in some regions affecting the herbs differently.

The drink sells well during summer, but there is particularly high demand in the Muslim fasting month of Ramadan. Around the dinner table, or in the bazaars at the end of a day, a glass or two of chilled Rooh Afza — the smack of its sugar and flavors — can inject life.

“During the summer, after a long and hot day of fasting, one becomes more thirsty than hungry,” said Faqir Muhammad, 55, a porter in Karachi, Pakistan. “To break the fast, I directly drink a glass of Rooh Afza after eating a piece of date to gain some energy.”

In Bangladesh, the brand’s marketing goes beyond flavor and refreshments and into the realms of the unlikely and the metaphysical.

“Our experts say Rooh Afza helps Covid-19-infected patients, helps remove their physical and mental weakness,” Amirul Momenin Manik, the deputy director of Hamdard Bangladesh, said without offering any scientific evidence. “Many people in Bangladesh get heavenly feelings when they drink Rooh Afza, because we brand this as a halal drink.”

During a visit to Rooh Afza’s India factory in April, which coincided with Ramadan, workers in full protective gowns churned out 270,000 bottles a day. The sugar, boiled inside huge tanks, was mixed with fruit juices and the distillation of more than a dozen herbs and flowers, including chicory, rose, white water lily, sandalwood and wild mint.

At the loading dock in the back, from dawn to dusk, two trucks at a time were loaded with more than a 1,000 bottles each and sent off to warehouses and markets across India.

Mr. Ahmed — who runs Hamdard’s food division, for which Rooh Afza remains the central product — is trying to broaden a mature brand with offshoots to attract consumers who have moved away from the sherbet in their teenage and young adult years. New products include juice boxes that mix Rooh Afza with fruit juice, a Rooh Afza yogurt drink and a Rooh Afza milkshake.

By Charukesi Ramadurai

“Cook and See” is just one of several community cookbooks from the decades when modern life began to displace multiple generations of women sharing the kitchen and dispensing wisdom as they prepared family meals. Through these books, the authors offered glimpses into their lives. For example, “Time & Talents Club Recipe Book” (1935) – packed with 2,000 recipes by a variety of contributors, sold as a fundraiser, and republished six times – is still held as the beacon for Parsi cooking, a meat-rich cuisine shaped by influences from Persia, where the community comes from, and from Gujarat, the Indian state they first called home in India. “Rasachandrika” (1943) by Ambabai Samsi featured recipes from the Saraswat Brahmin community on the western Konkan coast.

These cookbooks by homemakers for homemakers were compilations of not only recipes but also practical information – from essential cooking to festival rituals and home remedies for common ailments. Each community in India had, and still has, its own unique ingredients, techniques, recipes, and eating rituals, and these collections ensured this knowledge was passed down through the generations.

Somewhere in the late 1980s, however, Indian cuisine began to be seen and represented globally and nationally as one homogeneous curried red mass. Perhaps it was because the flavors of garlic naan and chicken tikka masala (a dish most Indians have never heard of) traveled well across continents and palates, or perhaps because the Punjabi people successfully managed to showcase their cuisine wherever they went. But the result was that representations of Indian food were cleaved into two neat south and north divisions as far as restaurant cooking was concerned. Regional cuisines and their cookbooks began to be relegated to the kitchens of more discerning home chefs or they were carried abroad by Indian students dreaming of their mother’s culinary creations.

But regional Indian cuisine is being rediscovered and celebrated once again through trendy pop-up brunches and specialty restaurants. More important, a growing number of regional cookbook writers are publishing new cookbooks, complete with easy but largely unknown recipes and glossy photographs highlighting regional spices, legumes, millets, oils, and grains.

“We have begun looking inwards rather than taking our cues from the West on what to eat,” says food writer Rushina Munshaw-Ghildiyal, referring to the recent Indian craze for kale and quinoa. “Now many of us are interested again in local ingredients, and are curious about how other people in our country eat.” And like their predecessors, these books offer glimpses of hidden cultures – culinary and otherwise – to a larger audience.

Take for instance, Lathika George’s book “The Suriani Kitchen” (2009). It is a rich repository of recipes from the small community of Syrian Christians in Kerala, whose cuisine is known for its extensive use of meat and seafood as well as coconut and local spices such as black pepper. It also serves as a cultural explainer – from typical community Christmas rituals to unique utensils, such as mann chatti (mud pots). Similarly, “Five Morsels of Love” by Archana Pidathala (2016) is a compilation of heirloom recipes from the southern Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, known for its extensive use of fiery, red chili, and the plethora of dry chutneys and spice powders. The more recent “Pangat, a Feast: Food and Lore from Marathi Kitchens” (2019) by Saee Koranne-Khandekar documents the versatility of cuisine from the various communities within the state of Maharashtra.

The transition from his tech job to running a restaurant wasn’t simple, but Romy says he was willing to learn the ropes. Gursewak, who always had a streak of independence, liked being a truck driver but he also wanted to be a businessman. He eventually put truck driving on hold to study business administration at Chabot College. Fast forward to the present, Gursewak and Romy can be found at one of their store locations most days where they oversee pizza production or prepare the pies themselves.

-----------

Gursewak Gill was visiting his in-laws in Canada when something suddenly clicked. Throughout the trip, pizza was for dinner most nights and Gursewak often found himself sprucing up the pies with a mix of green chilies, ginger, garlic and a blend of Indian spices. Before he knew it, his curiosity would be the stepping stone to his mini-chain Indian pizza empire, Curry Pizza House.

“When we came back [to California] I started experimenting at the house and adding Indian spices ... to make it more flavorful. Curry Pizza House was born from that point,” Gursewak said.

Since 2015, Curry Pizza House has taken up shop throughout the Bay Area with its first outpost in Fremont. Earlier this month, Gursewak and his business partner Gurmail “Romy” Gill (of no relation) opened a store in San Ramon, marking their 11th Curry Pizza House location, with more locations on the way in Texas.

Just before Gursewak and Romy became business partners in 2013, Gursewak founded Bombay Pizza House. After some thought, they deciding to form a restaurant model focused on curries inspired by their family recipes, eventually rebranding to Curry Pizza House.

"We want to be hands-on all the time to make sure that our customers get good quality, spicy food all the time,” Gursewak said.

The restaurants offer pizzas that highlight Indian ingredients, like the chicken tikka pizza and shahi paneer pizza, among others. Romy says there’s something for everyone on the menu because, in addition to the craft curry pizzas, they also sell classic American pies like combination and Hawaiian, with vegan and gluten-free options also on hand.

Curry Pizza House is among a small group of pizzerias slinging Indian pies around the bay. Among one of the most recognizable Indian pizzerias is Zante Pizza & Indian Cuisine, which has been a San Francisco staple since 1986. Zante Pizza, owned by Dalvinder Multani, is widely believed among its devoted customer base to be the first restaurant to create Indian pizza.

“A lot of people ask me: 'Do they have pizza like this in India?'" Multani told Vice in 2015. "No! That was only born here. That happens only here."

While the origins of Indian pizza are open for debate, its immediate success is not. When Gursewak thinks about Indian pizza, he likens it to dipping warm naan into butter chicken or different curry sauces. The depth of flavors Indian pizza delivers were a hit with Bay Area locals, and since the 1980s other local Indian pizzerias have opened up shop such as Golden Gate Indian Cuisine & Pizza in San Francisco and Pizza & Curry in Fremont.

Gursewak and Romy, who are both native to India, moved to Fremont in the mid-1990s, where they attended high school. Their trajectory into the pizza business wasn’t a straight path. Romy had been employed at DELL as a program manager for 15 years, while Gursewak worked at a truck driver with an intent to run a trucking business. Romy admits that he never wanted to be an engineer despite getting his degree in electronic and mechanical engineering at the now shuttered ITT in Hayward.

By RIAZAT BUTT

https://apnews.com/article/business-lahore-fa0ff330d1bff1386da77bb0815ae040

LAHORE, Pakistan (AP) — No menu. No delivery. No walk-ins. Advance orders only. Explanations and instructions while you eat.

Welcome to Baking Virsa, a hole-in-the-wall in the eastern Pakistani city of Lahore described as the country’s most expensive restaurant for what it serves — household favorites like flatbreads and kebabs.

It attracts diners from across Pakistan and beyond, curious about the limited offerings, the larger-than-life owner, and the rigid, no-frills dining experience that sets it apart from other restaurants in the area.

The windowless space opens out onto Railway Road in Gawalmandi, a neighborhood crammed with people, vehicles, animals, and food stalls. Restaurants belch out smells of baking bread, frying fish, grilling meats, and opinionated spicing into the early hours of the morning, when preparations begin for breakfast.

Lahore is a culinary powerhouse in Pakistan and, for years, Gawalmandi was famous for having a pedestrian area with restaurants and cafes.

Many of Gawalmandi’s original communities migrated from Kashmir and eastern Punjab province before partition in 1947, when India and Pakistan were carved from the former British Empire as independent nations. The mix of Hindus, Sikhs and Muslims enriched Gawalmandi’s commerce, culture and cuisine.

Some upscale parts of Lahore used to see Gawalmandi as “virtually a no-go area,” said Kamran Lashari, the director-general of the Lahore Walled City Authority. But a makeover more than 20 years ago helped pull in the crowds and turn it into a magnet for diners.

“We had street performers. President Pervez Musharraf sat in the street with people all around him. The prince of Jordan also visited. Indian newspapers reported on Gawalmandi,” Lashari said.

Restaurants in the neighborhood tend to be cheap and cheerful places.

And then there is Baking Virsa, where dinner for two can quickly come to $60 without drinks because drinks, even water, are not served. By comparison, a basket of naan at the five-star Serena Hotel in the capital, Islamabad, sells for a dollar and a plate of kebabs is $8. In Gawalmandi, one naan usually costs as little as 10 cents.

There are five items in Baking Virsa’s repertoire: chicken, chops, two types of naan, and kebabs. Owner Bilal Sufi also does a roaring trade in bakarkhani, buttery, savory, crispy pastry discs best enjoyed with a cup of pink Kashmiri chai. Everything is available for takeaway but must be ordered days in advance, even when dining in.

It is not a restaurant but a tandoor, a large oven made of clay, the 34-year-old Sufi tells people. It has been in the same location for 75 years, serving the same items for decades.

Sufi says he is only doing what his father and grandfather have done, detailing his marinade ingredients, cooking methods, meat provenance and animal husbandry. His sheep are fed a diet of saffron milk, dates and unripe bananas.

He also tells people how to eat their food. “Pick it up with your hands! Take a big bite! Eat like a beast!” he urges them.

By RIAZAT BUTT

https://apnews.com/article/business-lahore-fa0ff330d1bff1386da77bb0815ae040

There is no salad, no yogurt, and no chutney, he tells a potential customer on the phone. “And if you ask for these you won’t get them.”

Sufi has run Baking Virsa for more than three years, taking over from his father Sufi Masood Saeed, who ran it before him and his grandfather Sufi Ahmed Saeed before that.

“In Pakistan, people think the spicier the better,” said the third-generation tandoor owner. “Everywhere in Pakistan you’ll have sauce or salad. If you have those on your taste buds, will you taste the yogurt or the meat?”

The meal arrives in a sequence.

First, Sufi presents a whole chicken, for $30, followed by mutton chops at $12.50, then a kebab, which costs $8. Sufi says one kebab is enough for two people. A female diner asks for a plain naan with her chicken but is told she can’t have it until she gets her kebab.

Her companion asks for a second kebab but is declined.

“All our kebabs are committed,” Sufi tells him solemnly.

Another diner wants the mutton-stuffed naan but is told she can’t have it as it wasn’t part of the telephone order made three nights earlier.

Dinner comes on plastic plates atop plastic stools to a soundtrack of tooting rickshaws and other street life. Neighbors complain that the SUVs and sleek cars with Islamabad license plates block their doorways. Nobody moves their vehicles.

Sufi is unapologetic about everything. If he doesn’t get the quality of meat he wants, he won’t serve it. He’ll cancel the order and return the money to customers.

If there aren’t enough orders, he won’t open on that particular day.

“It isn’t necessary to open every day,” he says. “We need to fulfil a minimum quantity for the recipes, that’s 10-12 people.”

He insists on his customers knowing what they eat, where it comes from, how it’s made — and “why it tastes so different.”

Baking Virsa, like the properties surrounding it, has no gas or running water. There is little to no street lighting on Railway Road. Any illumination comes from traffic, homes, and businesses. Away from the lip-smacking aroma of food, there is the occasional whiff of sewage.

Lashari, the city official, laments the “decay and disorder” that blights Gawalmandi and other traditional neighborhoods like it. He says they have a lot of commercial, residential and tourism potential but need an urban regeneration program.

Sufi, unperturbed by his very basic surroundings, has no intention of changing anything.

“Baking Virsa is a legacy,” he says. “I’m doing this out of love and affection for my father.”

https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-36548445

We don't know for certain when the first cooks shaped pastry into the now-familiar triangular shape but we do know that the origins of the name are Persian - "sanbosag".

The samosa is first mentioned in literature by the Persian historian Abul-Fazl Beyhaqi, writing in the 11th Century.

He describes a dainty delicacy, served as a snack in the great courts of the mighty Ghaznavid empire. The fine pastry was filled with minced meats, nuts and dried fruit and then fried till the pastry was crisp.

But the samosa was to be transformed as it followed the epic journey made by successive waves of migrants into India.

It was brought to India along the route the Aryans had taken more than 2,000 years earlier - through Central Asia and then over the great mountains in what is now Afghanistan, before descending down into the fertile plains of the great rivers of India.

The great armies of the Mamluks, Tamerlane and the Mughals later made the same journey, helping build the great sub-continental empire we now know as India.

And, just as India was reshaped by these waves of migrants, the samosa also underwent a transformation.

Initially it metamorphosed into something much less refined.

By the time it reached what is now Tajikistan and Uzbekistan it had become what Professor Pushpesh Pant, one of the world's experts on Indian food, describes as "a crude peasant dish".

The courtly titbit was now a high-calorie staple, a much bigger and heartier dish - the sort of thing a shepherd would take out into the pastures with him.

It retained its distinctive shape and was still fried, but the exotic nuts and fruits were gone - the savoury pastry was now filled with coarsely chopped goat or lamb eked out with onions and flavoured simply with salt.

Over the following centuries the samosa made its way over the icy passes of the Hindu Kush and into the Indian subcontinent.

What happened along the way explains why Professor Pant regards the samosa as the ultimate "syncretic dish" - the ultimate fusion of cultures.

A Glasgow restaurateur, he was part of the rise of the British curry house — and played an essential part in its story.

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/22/dining/ali-ahmed-aslam-dead.html

Ali Ahmed Aslam, the Glasgow restaurateur who was often credited with the invention of chicken tikka masala, died on Monday. He was 77.

His son Asif Ali said the cause was septic shock and organ failure after a prolonged illness. He did not say where Mr. Aslam died.

Much like Cartesian geometry, chicken tikka masala was most likely not one person’s invention, but rather a case of simultaneous discovery — a delicious inevitability in so many restaurant kitchens, advanced by shifting forces of immigration and tastes in postwar Britain.

Many cooks claimed that they were the ones who served it first, or that they knew a guy who knew the guy who really did. Others insisted it wasn’t a British invention at all but a Punjabi dish. None of those stories seemed to stick.

Instead, the bright tomato-tinted lights of fame shone on one man: Mr. Aslam, who immigrated to Glasgow from a village outside Lahore, Pakistan, when he was 16, and who opened the restaurant Shish Mahal in 1964.

What seems to have established Mr. Aslam as the inventor of the dish was an unsuccessful 2009 bid by the Scottish member of Parliament Mohammad Sarwar to have the European Union recognize chicken tikka masala as a Glaswegian specialty. In an interview with Agence France-Presse, Mr. Aslam explained that he had added some sauce to please a customer once, and you could almost hear him shrug.

In Aslam family lore, it was a local bus driver who popped in for dinner and suggested that plain chicken tikka was too spicy for him, and too dry — and also he wasn’t feeling well, so wasn’t there something sweeter and saucier that he could have instead? Sure, why not. Mr. Aslam, who was known as Mr. Ali, tipped the tandoor-grilled pieces of meat into a pan with a quick tomato sauce and returned them to the table.

“He never really put so much importance on it,” Asif Ali said. “He just told people how he made it.”

Chicken tikka masala became so widespread that in 2001 Robin Cook, the British foreign secretary, delivered a speech praising the dish — and Britain for embracing it.

“Chicken tikka masala is now a true British national dish,” Mr. Cook said, referring to a survey that had placed it above fish and chips in popularity. “Not only because it is the most popular, but because it is a perfect illustration of the way Britain absorbs and adapts external influences.”

Mr. Aslam was born into a family of farmers, in a small village near Lahore. As a teenager, newly arrived to Glasgow in 1959, he took a job with his uncle in the clothing business during the day and cut onions at a local restaurant at night.

Mr. Aslam was ambitious, and he soon opened his own place in the city’s West End. He installed just a few tables and a brilliantly hot well of a tandoor oven, which he learned to man in a sweaty process of trial and error. He brought his parents over from Pakistan; his mother helped to run the kitchen, and his father took care of the front of the house.

In 1969, Mr. Aslam married Kalsoom Akhtar, who came from the same village in Pakistan. In Glasgow they raised five children. In addition to his son Asif, his survivors include his wife; their other children, Shaista Ali-Sattar, Rashaid Ali, Omar Ali and Samiya Ali; his brother Nasim Ahmed; and his sisters Bashiran Bibi and Naziran Tariq Ali.

Chicken tikka masala boomed in the curry houses of 1970s Britain. Soon it was more than just a dish you could order off the menu at every curry house, or buy packaged at the supermarket; it was a powerful political symbol.

https://cooking.nytimes.com/recipes/1023892-chicken-manchurian

A stalwart of Pakistani Chinese cooking, chicken Manchurian is immensely popular at Chinese restaurants across South Asia. This recipe comes from attempts at recreating the version served at Hsin Kuang in Lahore, Pakistan, in the late ’90s. At restaurants it’s almost always served on a sizzler platter, the tangy, sweet-and-sour sauce bubbling and thickening on its way to the table. Making it at home doesn’t compromise any of the punchy flavors. Velveting the chicken in egg and cornstarch means it’ll stay tender through the short cooking process; bell pepper and spring onions add freshness and crunch to the otherwise intense flavors from ketchup and chile-garlic sauce.

-------------

Whose Chicken Manchurian is it anyway? Pakistan's or India's?

https://www.wionews.com/entertainment/lifestyle/news-whose-chicken-manchurian-is-it-anyway-pakistans-or-indias-576353

A recently published recipe by The New York Times referred to chicken manchurian as a "stalwart of Pakistani Chinese cooking". The NYT recipe mentions that the dish comes from "attempts at recreating the version served at Hsin Kuang in Lahore, Pakistan, in the late '90s". The recipe mentioned that the dish was almost always served on a sizzler platter.

But was chicken manchurian really invested in Pakistan? There's definitely a dispute. When we follow the recipe, in an attempt to cook it, several media reports call it a Chinese recipe, some call it Indo-Chinese.

A report published in 2017 by the South China Morning Post (SCMP) talks about How chicken manchurian found its place in Indian cuisine. It mentioned that chicken manchurian was apparently created by Nelson Wang, a third-generation Chinese chef born in India. But also admitted that there is little dispute over the origin as it is often difficult to trace the exact origins of a dish.

The SCMP report stated that the dish was believed to have been created in Mumbai by Wang, who was born in Kolkata (then known as Calcutta). The report mentioned that the dish was invented by Wang when he was a chef at the Cricket Club of India, in Mumbai. He even opened his restaurant in 1983 in China Garden and it is now a chain with outlets throughout India and Nepal.

Chicken manchurian is prepared with pieces of chicken coated in a soy sauce mixture and pan-fried until crisp with a thick sauce of ginger, garlic and green chillies. It is then added to a soy sauce gravy and sometimes vinegar and ketchup. It is mostly served with rice or noodles.

The debate may also include the vegetarian version like Gobi manchurian, veg manchurian, and paneer manchurian. So next time, when you gulp a bite of this luscious dish, do think about its origins rather than only enjoying the punchy flavours.