India's Debt Up, Forex Reserves Down

India’s total external public debt has risen to $326 billion while foreign exchange reserves have dropped to $293 billion, according to the RBI data reported by the Indian Express newspaper.

The Reserve Bank of India is concerned over the increasing shift from equity to debt to fill India's widening current account gap. The latest available data indicates that foreign debt inflows in January so far have amounted to $3.21 billion versus $1.7 billion through equity inflows.

Recent $1.1 billion bail-out of Reliance Communications by state-owned Chinese banks is the clearest indication yet that the situation is also becoming dire in India's private sector with its mounting foreign debt.

This is not the first instance of Chinese banks coming to the aid of an Indian company. Last November, Sasan Power, the project company for the Sasan ultra mega power plant and a subsidiary of RComm affiliate Reliance Power, completed a $2.2 billion refinancing, including a $1.114 billion 13-year tranche. Bank of China, CDB and Chexim took $1.06 billion of that tranche, for which Chinese export credit agency Sinosure provided insurance.

Reliance Com is not alone in facing cash crunch in their ability to service debt. More than two dozen Indian companies included in the BSE-500 index face redemptions on foreign currency convertible bonds worth a combined Rs330 billion ($6.5 billion) by March 2013, according to brokerage Edelweiss. These include RComm’s US$925m outstanding CB, which the loan will repay.

Unless other Indian borrowers can somehow find lenders, they will be facing deteriorating debt market conditions that have led to shrinking liquidity in the loan markets and a rise in pricing.

“Top-tier Indian firms will have to pay between 250 basis points (2.5%) and 300 basis points (3.0%) over LIBOR (London Inter-bank Borrowing Rate) to borrow five-year money offshore. Even at that kind of pricing, there isn’t a lot of liquidity available,” said a Hong Kong-based lender quoted by International Financing Review. Over $20 billion worth of Indian debt is set to mature in 2012 and, of that, about $6 billion each of convertible bonds and rupee loans are up for redemption, with the balance in offshore loans.

India continues to run huge twin deficits of current account and budget. It depends heavily on foreign inflows. United Nations data shows that India received less than $20 billion in FDI in the first six months of 2011, compared to more than $60 billion in China while Brazil and Russia took in $23 billion and $33 billion respectively. Stocks in all four countries have underperformed relative to the broader emerging markets equity index, as well as the markets in the developed nations. Pakistan's KSE-100 has significantly outperformed all BRIC stock markets over the ten years since BRIC was coined.

Noting India's significant dependence on foreign capital inflows, Jim O'Neill recently raised concern about the potential for current account crisis. "India has the risk of ... if they're not careful, a balance of payments crisis. They shouldn't raise people's hopes of FDI and then in a week say, 'we're only joking'". "India's inability to raise its share of global FDI is very disappointing," he said.

In addition to Jim O'Neill, a range of investment bankers are turning bearish on India. UBS sent out an email headlined "India explodes" to its clients. Deutsche Bank published a report on November 24 entitled, "India's time of reckoning."

"Suddenly everything seems to be coming to a head in India," UBS wrote. "Growth is disappearing, the rupee is in disarray, and inflation is stuck at near-record levels. Investor sentiment has gone from cautious to outright scared."

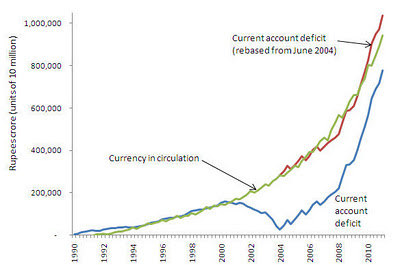

India's current account deficit swelled to $14.1 billion in its fiscal first quarter, nearly triple the previous quarter's tally. The full-year gap is expected to be around $54 billion.

Its fiscal deficit hit $58.7 billion in the April-to-October period. The government in February projected a deficit equal to 4.6 percent of gross domestic product for the fiscal year ending in March 2012, although the finance minister said on Friday that it would be difficult to hit that target.

As explained in a series of earlier posts here on this blog, India has been relying heavily on portfolio inflows -- foreign purchases of shares and bonds -- as a means of covering its rising current account gap. Those flows are called "hot money" and considered highly unreliable.

Indian policy makers face a significant dilemma. If they do nothing to defend the Indian currency, the downward spiral could make domestic inflation a lot worse than it already is, and spark massive civil unrest. If they intervene in the currency market aggressively by buying up Indian rupee, the RBI's dollar reserves could decline rapidly and trigger the balance of payment crisis Goldman Sachs' O'Neill hinted at.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

India Disappoints Goldman Sachs

India's Twin Deficits

Karachi Tops Mumbai in Stock Performance

India Returning to Hindu Growth Rate

Soft or Hard Landing For Indian Economy?

Karachi Stocks Outperform Mumbai, BRICs

The Reserve Bank of India is concerned over the increasing shift from equity to debt to fill India's widening current account gap. The latest available data indicates that foreign debt inflows in January so far have amounted to $3.21 billion versus $1.7 billion through equity inflows.

Recent $1.1 billion bail-out of Reliance Communications by state-owned Chinese banks is the clearest indication yet that the situation is also becoming dire in India's private sector with its mounting foreign debt.

This is not the first instance of Chinese banks coming to the aid of an Indian company. Last November, Sasan Power, the project company for the Sasan ultra mega power plant and a subsidiary of RComm affiliate Reliance Power, completed a $2.2 billion refinancing, including a $1.114 billion 13-year tranche. Bank of China, CDB and Chexim took $1.06 billion of that tranche, for which Chinese export credit agency Sinosure provided insurance.

Reliance Com is not alone in facing cash crunch in their ability to service debt. More than two dozen Indian companies included in the BSE-500 index face redemptions on foreign currency convertible bonds worth a combined Rs330 billion ($6.5 billion) by March 2013, according to brokerage Edelweiss. These include RComm’s US$925m outstanding CB, which the loan will repay.

Unless other Indian borrowers can somehow find lenders, they will be facing deteriorating debt market conditions that have led to shrinking liquidity in the loan markets and a rise in pricing.

“Top-tier Indian firms will have to pay between 250 basis points (2.5%) and 300 basis points (3.0%) over LIBOR (London Inter-bank Borrowing Rate) to borrow five-year money offshore. Even at that kind of pricing, there isn’t a lot of liquidity available,” said a Hong Kong-based lender quoted by International Financing Review. Over $20 billion worth of Indian debt is set to mature in 2012 and, of that, about $6 billion each of convertible bonds and rupee loans are up for redemption, with the balance in offshore loans.

India continues to run huge twin deficits of current account and budget. It depends heavily on foreign inflows. United Nations data shows that India received less than $20 billion in FDI in the first six months of 2011, compared to more than $60 billion in China while Brazil and Russia took in $23 billion and $33 billion respectively. Stocks in all four countries have underperformed relative to the broader emerging markets equity index, as well as the markets in the developed nations. Pakistan's KSE-100 has significantly outperformed all BRIC stock markets over the ten years since BRIC was coined.

Noting India's significant dependence on foreign capital inflows, Jim O'Neill recently raised concern about the potential for current account crisis. "India has the risk of ... if they're not careful, a balance of payments crisis. They shouldn't raise people's hopes of FDI and then in a week say, 'we're only joking'". "India's inability to raise its share of global FDI is very disappointing," he said.

In addition to Jim O'Neill, a range of investment bankers are turning bearish on India. UBS sent out an email headlined "India explodes" to its clients. Deutsche Bank published a report on November 24 entitled, "India's time of reckoning."

"Suddenly everything seems to be coming to a head in India," UBS wrote. "Growth is disappearing, the rupee is in disarray, and inflation is stuck at near-record levels. Investor sentiment has gone from cautious to outright scared."

India's current account deficit swelled to $14.1 billion in its fiscal first quarter, nearly triple the previous quarter's tally. The full-year gap is expected to be around $54 billion.

Its fiscal deficit hit $58.7 billion in the April-to-October period. The government in February projected a deficit equal to 4.6 percent of gross domestic product for the fiscal year ending in March 2012, although the finance minister said on Friday that it would be difficult to hit that target.

As explained in a series of earlier posts here on this blog, India has been relying heavily on portfolio inflows -- foreign purchases of shares and bonds -- as a means of covering its rising current account gap. Those flows are called "hot money" and considered highly unreliable.

Indian policy makers face a significant dilemma. If they do nothing to defend the Indian currency, the downward spiral could make domestic inflation a lot worse than it already is, and spark massive civil unrest. If they intervene in the currency market aggressively by buying up Indian rupee, the RBI's dollar reserves could decline rapidly and trigger the balance of payment crisis Goldman Sachs' O'Neill hinted at.

Related Links:

Haq's Musings

India Disappoints Goldman Sachs

India's Twin Deficits

Karachi Tops Mumbai in Stock Performance

India Returning to Hindu Growth Rate

Soft or Hard Landing For Indian Economy?

Karachi Stocks Outperform Mumbai, BRICs

Comments

ahmedabadonnet.com

It is not a secret to longtime readers of this blog that I rate India’s prospects far more pessimistically than I do China’s. My main reason is I do not share the delusion that democracy is a panacea and that whatever advantage in this sphere India has is more than outweighed by China’s lead in any number of other areas ranging from infrastructure and fiscal sustainability to child malnutrition and corruption. However, one of the biggest and certainly most critical gaps is in educational attainment, which is the most important component of human capital – the key factor underlying all productivity increases and longterm economic growth. China’s literacy rate is 96%, whereas Indian literacy is still far from universal at just 74%.

-----------

The big problem, until recently, was that there was no internationalized student testing data for either China or India. (There was data for cities like Hong Kong and Shanghai, but it was not very useful because they are hardly representative of China). An alternative approach was to compare national IQ’s, in which China usually scored 100-105 and India scored in the low 80′s. But this method has methodological flaws because the IQ tests aren’t consistent across countries. (This, incidentally, also makes this approach a punching bag for PC enforcers who can’t bear to entertain the possibility of differing IQ’s across national and ethnic groups).

--------------

Many Indians like to see themselves as equal competitors to China, and are encouraged in their endeavour by gushing Western editorials and Tom Friedman drones who praise their few islands of programming prowess – in reality, much of which is actually pretty low-level stuff – and widespread knowledge of the English language (which makes India a good destination for call centers but not much else), while ignoring the various aspects of Indian life – the caste system, malnutrition, stupendously bad schools – that are holding them back. The low quality of Indians human capital reveals the “demographic dividend” that India is supposed to enjoy in the coming decades as the wild fantasies of what Sailer rightly calls ”Davos Man craziness at its craziest.” A large cohort of young people is worse than useless when most of them are functionally illiterate and innumerate; instead of fostering well-compensated jobs that drive productivity forwards, they will form reservoirs of poverty and potential instability.

Instead of buying into their own rhetoric of a “India shining”, Indians would be better served by focusing on the nitty gritty of bringing childhood malnutrition DOWN to Sub-Saharan African levels, achieving the life expectancy of late Maoist China, and moving up at least to the level of a Mexico or Moldova in numeracy and science skills. Because as long as India’s human capital remains at the bottom of the global league tables so will the prosperity of its citizens....

http://www.sublimeoblivion.com/2012/02/04/china-superior-to-india/

The question is when would the risk aversion trades come off and what could trigger them? Greek elections are in mid June and talks of Greece exiting the Euro will persist. Economic data in the form of better employment numbers in the US and better manufacturing growth across geographies could provide relief to markets. Read More...

http://investorsareidiots.com/2012/05/weekly-equity-market-analysis-week-ended-18th-may-2012/

INDIA’S economy has had some bad economic ideas inflicted on it over the past century, from imperial neglect to the cult of the village and big-ticket socialism. Maybe the concept of BRICs—a handful of emerging economies including India that were destined for fast growth—should be added to the list. It led to a bubble of complacency that is now being popped rather brutally. Growth in India was 5.3% in the three months to March—worse than the 6% expected, below the prior quarter and way below the close-to-double digit rates that were meant to be preordained and propel India to economic super-power status.

Other BRICs have slowed too, including China and Brazil. But India's GDP figures, the worst for at least nine years, will have a deep impact on the sub-continent. The country was meant to grow in its sleep—regardless of what happens in the rest of the world. A quick bounce back looks unlikely. The central bank has cut interest rates a little this year, but will struggle to loosen policy further given high inflation. The ruling coalition keeps on promising a bout of reforms to boost confidence, but it is so divided, its behaviour so erratic and its record of delivery so poor that few believe this will actually happen. Expectations for growth over the next couple of years will probably slip further, to 6%.

A 6%-growth-India raises three issues. For one, the old orthodoxy was that after liberalisation India had been on an accelerating path, driven by demographics and its high rate of savings and investment. A rival view is now likely to take hold. It notes that India has grown pretty consistently at 6% since the mid 1980s, with the exception of a faster period in 2004-2007. What looked like a step up in trajectory now looks like a one-off blip driven by a global boom, an uncharacteristic bout of tight fiscal policy and an unsustainable burst of corporate optimism. Political history may have to be rewritten too. The reformers of 1991, who include the present prime minister, have turned out to be not visionaries, but pragmatists without a deep commitment to liberalisation who have been unable to build a lasting consensus among voters and the political class in favour or reform.

Second, financial stability will become trickier. Nominal GDP growth (including inflation) has slipped to the low teens. This is still above the rate of interest India's government pays on its debt and thus in theory enough to avoid a debt spiral—despite high fiscal deficits running at almost a tenth of GDP. Government bond yields are artificially depressed because banks are forced to buy government paper and because the central bank has been buying bonds actively in the last six months. Although this can go on for a while, the stress is showing up in two different areas. One is the banking system where gross bad debts plus "restructured" loans have risen to over 8% of the total—a figure high even by western banks' standards. Bankers and the central bank argue that "restructured" loans are unlikely to result in large losses. But with lower growth more corporate borrowers will come under strain, as will the credibility of those reassurances.

----------

Perhaps growth will bounce back. And if it doesn't, perhaps public frustration will be expressed at the ballot box, creating a new, less complacent political climate. The view that India's democracy is a self correcting mechanism that steers the country back onto the right course when things go wrong, was an integral part of the bulls' view of India. Hopefully it is one idea from the boom that proves to be correct.

http://www.economist.com/blogs/newsbook/2012/05/indias-economy

India's growth prospects have been fading for some time. Multinationals are walking away from the country, withdrawing some $10.7 billion worth of investments in 2011 alone, according to Nomura. Manufacturing contracted by 0.3% for the year that ended March 31. Agriculture and services faltered as well.

-------------

Delhi managed to keep the party going after the 2008 financial crisis with more government spending and easier credit. But that only postponed the reckoning—while sending the inflation rate north of 8% for the better part of the last two years.

After growth dipped below 7% late last year, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh turned to gimmicks, like having state-owned Coal India boost coal supply to power producers in a one-off manner or proposing to set up special manufacturing zones where factories would get tax breaks. But businesses want less red tape permanently, especially when it comes to energy investments, as well as labor reform to make hiring and firing easier. On both fronts, the Prime Minister has done nothing.

Then there was his one serious attempt at reform. In late November he announced plans to allow foreign investment in big-box retail stores. The reform would have been a boon for consumers, and would have helped import some crucial supply-chain know how. But the reform met the usual combination of populist and special-interest resistance, and the government folded in 10 short days.

Indians are increasingly disenchanted with Congress's failure to push for pro-market reforms, and have voted accordingly in recent state elections. That's the good news. There's been a lot of talk about India's emergence as a new economic superpower. An India with the ambition to rise in the world will not treat a high-growth economy as a national birthright.

http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052702303640104577440103460087194.html

July 8, 2013:

India’s international investment position (IIP) saw significant deterioration in the year-ended March 31, 2013. The country’s net liabilities to other countries rose by $57.8 billion to $307.8 billion over the course of the year. This caused the net IIP to worsen from a negative 14 per cent of GDP to a negative 16.7 per cent.

The International Investment Position compares what India owes to entities located overseas (liabilities) relative to what it is owed by foreign entities (assets). In recent years, India’s liabilities have been expanding while assets have stagnated.

FDI DOWN

Liabilities have soared on the back of exporters taking more short term credit, and loans and deposits flowing in from overseas. A break-up of the country’s international liabilities indicates that overseas trade credit, loans and deposits extended to India, grew by 13.8 per cent in 2012-13 from 2011-12 levels. This amounted to 18.4 per cent of GDP in March 2013, up from 16.8 per cent in 2012-13.

This was a weak year for inbound foreign direct investments, which grew only by 5.1 per cent. Portfolio investment expanded by 10.4 per cent during the year. This was mainly in the form of equity inflows.

In contrast, Indian companies remained rather cautious about investing across the border. International assets — which capture investments in foreign currency — stagnated at 24.3 per cent of GDP compared to 24.5 per cent a year ago. This was driven by the 0.8 per cent decline in the foreign exchange reserves.

Portfolio investments by Indian companies fell by 6.6 per cent, but direct investments overseas rose by 6.3 per cent. This depicts the value of the country’s direct investment abroad, portfolio investments, equity and debt security investments, trade credits, loans and reserve assets, among others, as a proportion of its cumulative economic output in a given year.

The ratio of net foreign liabilities to GDP is regarded as an indicator of default risk. This indicates that the country’s liabilities to external parties have been rising as a proportion of its economic output.

http://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/india-owes-more-to-overseas-entities-now/article4895405.ece?ref=wl_industry-and-economy

NRI deposits amounted to $98.639 billion in December 2013, a clear increase of 107.7 per cent over the $47.490 billion in December 2009. These NRI deposits need to be repaid over the next two-three years.

The rising external debt number is bound to induce a sense of foreboding when viewed through the prism of critical macro ratios — the RBI’s total hoard of foreign exchange reserves can now service only 69 per cent of external debt (compared with 138 per cent in 2007-08), the total outstanding is 23.3 per cent of GDP (it has always been lower than this since 1998-99), and concesssional debt comprises only 10.6 per cent of total debt stock (which means a higher debt servicing burden).

Clearly, one of the objectives of the circular mentioned above — apart from avoiding the cosmetic transfer of risk from the domestic balance-sheet — is to keep a lid on external debt, especially since tapering by the US Fed Reserve is likely to keep the external economy volatile. Allowing Indian companies to raise funds overseas to repay domestic debt might aggravate the situation now.

RBI tightens the screws

The second purpose of the circular is to address the probable risks that might arise from short-term external debt, or loans to be repaid within 12 months. Short-term debt was 21.8 per cent of total debt as of December 2013, and is lower both as a percentage of total outstanding external debt as well as in absolute numbers compared to the immediate preceding months.

The country’s stock of short-term external debt touched $92.707 billion at end-December 2013, or close to 21.8 per cent of the total debt, compared with $91.881 billion in December 2012 comprising 24.4 per cent of total external debt then.

What could be worrying the RBI is the rush of money streaming into short term debt instruments — such as 91-day treasury bills issued by the government or commercial paper floated by companies. Such a deluge could be facilitated both by the interest rate differential between western markets and India, as well as the stronger rupee vis-à-vis the dollar.

One of the clear indicators to central bank strategy was revealed in RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan’s first bi-monthly policy statement of April 1. The RBI announced that henceforth foreign portfolio investors will not be allowed to invest in any government security, including treasury bills, with maturity less than a year. While the ceiling for investments in government securities remains fixed at $30 billion, the RBI wants it invested entirely in government paper with maturity of more than a year.

This, the bank hopes, will deter the yield-chasing, short-term investors and insulate the economy from volatility. To soften the blow, the apex bank has handed out portfolio investors a number of sweeteners that facilitate the process, and lower the cost, of investing in the Indian capital market.

One, portfolio investors can now open a local bank account and transfer investible capital into that account directly, unlike the earlier tedium of having to route funds through a custodian bank, which widened the time lag between intent and investment.

Also, portfolio investors can now hedge their currency risks in local exchanges, provided their investments are in government debt of more than 12 months maturity. This is bound to lower their costs, apart from providing them further inducement to invest in Indian paper.

http://www.samachar.com/no-external-debt-crisis-please-ofhvMzcdiib.html

India is set to miss its fiscal deficit target for the year ending March 2019 due to a shortfall in revenues and lower-than-targeted disinvestment proceeds, India Ratings and Research said on Monday.

The country's 2019 fiscal deficit target has been pegged at 3.3 percent of its gross domestic product (GDP) or 6.24 trillion rupees ($88.45 billion). But the credit rating agency estimated fiscal deficit at 6.67 trillion - or 3.5 percent of GDP.